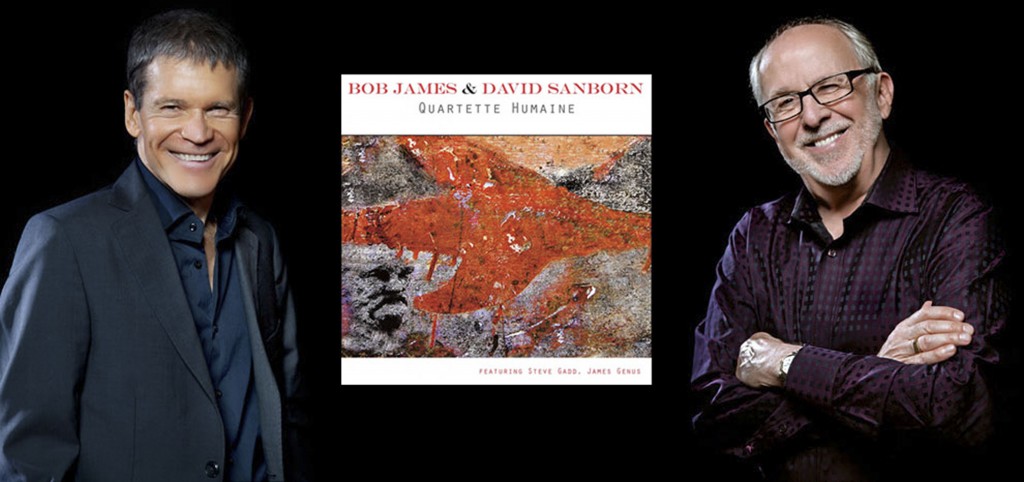

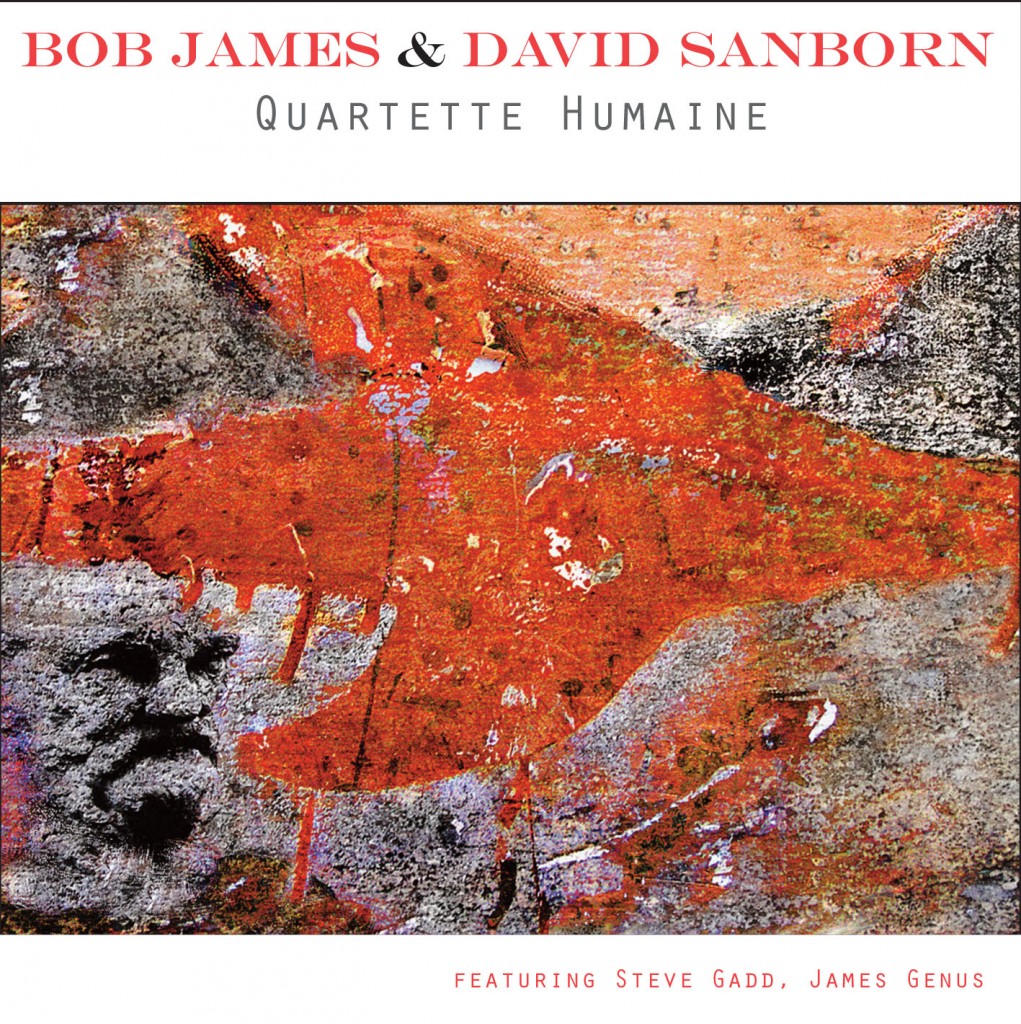

Jazz legends Bob James and David Sanborn pay tribute to the iconic Dave Brubeck Quartet on their new album Quartette Humaine, their first collaboration since their 1986 platinum-selling, Grammy Award-winning Double Vision disc. An all-acoustic project featuring bassist James Genus and drummer Steve Gadd, the album (released May 21) is the heart of an ambitious national tour featuring the four musicians with a launch planned at New York’s Town Hall June 6.

Jazz legends Bob James and David Sanborn pay tribute to the iconic Dave Brubeck Quartet on their new album Quartette Humaine, their first collaboration since their 1986 platinum-selling, Grammy Award-winning Double Vision disc. An all-acoustic project featuring bassist James Genus and drummer Steve Gadd, the album (released May 21) is the heart of an ambitious national tour featuring the four musicians with a launch planned at New York’s Town Hall June 6.

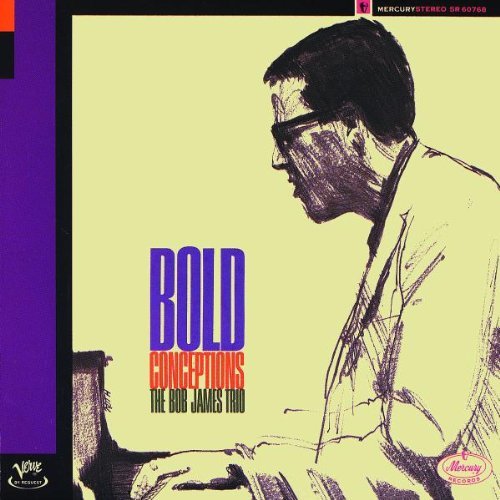

This year also marks the fiftieth anniversary of James’ discovery by Quincy Jones at the Notre Dame Jazz Festival and the recording of his first album as a leader, Bold Conceptions. Since that time, James has released 58 albums, with highlights including the international smash “Angela (Theme from Taxi)” and his long-running association with the jazz supergroup Fourplay.

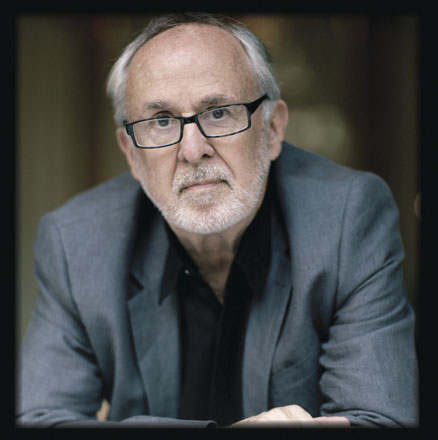

In part one of this exclusive, extended interview, I talked with James about his interactions with Brubeck, his long-awaited reunion with Sanborn, the profound love he has for his family, and his thoughts about his critics, partners and protégées in the jazz world.

The new album is kind of a tribute to Dave Brubeck, is that right?

The new album is kind of a tribute to Dave Brubeck, is that right?

We have been talking about it that way. It gives us a launching pad to be able to try to explain what our thought process was when we started. It’s not completely a tribute to Dave, but when we first had our discussions, we were thinking that we definitely did not want to do just a Double Vision Revisited. David and I have not collaborated, believe it or not, since 1986 with the Double Vision record—we never toured during that time. And it’s a long story why that didn’t happen, but it just never did. And we have encountered each other many times on the road and we have remained friends for the duration, but every time that we talked about doing a follow-up, somehow for one reason or another it never happened, and before we knew it, a large chunk of time had passed.

Starting last year, we both said, we just have to do this; we have a responsibility. [Double Vision] was a very big success for both of us, and it changed our lives and our careers, and there’s some kind of a responsibility to follow up. So having decided that we did not want to just try to recreate that sound, what would we do? And for both of us, it seemed a very interesting creative idea to strip down to a very acoustic kind of sound that was minimally produced in the sense of adding other elements to it, and we arrived at what is the classic quartet instrumentation. And because Dave [Sanborn] plays the alto sax and I play the piano, and we brought out the acoustic bass and drums, we found ourselves confronted with the idea that the most classic ensemble with that instrumentation was Dave Brubeck’s quartet featuring Paul Desmond. And so, that was our launching pad.

We used it as a reference point not from thinking that we wanted to try to mimic their style or anything like that, but just more giving us a place to start. And after that we went into the studio in December, and an amazing coincidence happened that Dave Brubeck passed away during the very day that we were making our recording. So then it became even more of a feeling of fate, a feeling of responsibility to follow up on that idea. We ended up being very happy to describe this project as a kind of tribute to that era; it was a time where Dave and I were both growing up learning and listening to what was going on, and we were definitely influenced by the Dave Brubeck Quartet, along with many, many other people in that era.

Do you have any stories of meeting Mr. Brubeck?

Do you have any stories of meeting Mr. Brubeck?

Well, I do. I worked for several years as an A&R guy at Columbia [Records] before it became Sony, and Bruce Lundvall, who was president of Columbia at that time, had signed me there to become an A&R guy, and I got a custom label deal for my small label, Tappan Zee, that became a way for me to produce some records on my own. And during that time, Dave Brubeck’s sons were recording…Their group was recording for Columbia—I didn’t become directly involved in producing or anything like that, but I was a little bit involved in that era and got to meet Dave during that time.

And then many, many years went by after that, and about three or four years ago I was playing a concert down in Florida, and Dave Brubeck was also on the same bill. And we came backstage, and the promoter wanted to do a photograph of all of the musicians and Dave…I found myself standing next to Dave Brubeck and felt the obligation to introduce myself to him. And he immediately said, “Bob, we know each other—I met you many, many years ago!”

And I was so flattered that he remembered, even though we had never directly worked together. I actually was shocked that he knew who I was….I remember also being impressed that he was still active, still ambitious, still vital, still very much into performing, and I think he had either reached the ripe old age of 90 by then, or maybe he was flirting with it. I think he died when he was in his early nineties, and I view that as definitely an inspiration to want to keep going and keep being creative as long as I can.

He had such a joy of performing onstage, always smiling just like Tony Bennett. I can’t think of anyone else I’ve seen in concert who was always that ebullient onstage. I don’t know if you were aware of this, but he has not yet been inducted in New York’s Nesuhi Ertegun Jazz Hall of Fame at Lincoln Center.

He had such a joy of performing onstage, always smiling just like Tony Bennett. I can’t think of anyone else I’ve seen in concert who was always that ebullient onstage. I don’t know if you were aware of this, but he has not yet been inducted in New York’s Nesuhi Ertegun Jazz Hall of Fame at Lincoln Center.

Really?

It’s hard to believe.

It doesn’t completely surprise me, because there’s a little bit of a mafia aspect of that, that we all face in the arts, that everybody has their taste and their opinions, and whoever happens to be on the board making those decisions, they can’t cover everything, so they go with their favorites. And maybe Dave wasn’t one of them.

I asked George Avakian to put in a good word when I interviewed him a few years ago.

Good for you.

But we’re still waiting.

At your ripe young age of thirty-whatever it is, maybe you’ll put in a word for me somewhere down the line.

If I’m not mistaken, getting that thumbs up from the critical establishment never seemed to bother you that much.

No, and a little bit yes. I have accepted, like all people in the arts do, that the public decides what they think about what you do, and you’re only in control of your own work. And I have always felt that if I start to get too worried about what it is that makes someone or something acceptable or not, then I’m not being true to myself. I’m going on the basis of trying to figure out what somebody else thinks, and I have stayed pretty true to trusting my own instincts and allowing my listeners to decide whether it’s good or it isn’t good.

I have a very, very different idea about jazz than a lot of what the establishment has come to think is the most pure way to make jazz. I don’t agree with most of that, actually. But I accept the fact that they have just as much right to think and come to conclusions as I do, to just play my music and hope for the best.

It’s a thorny subject, but have you always considered yourself a jazz artist?

It’s a thorny subject, but have you always considered yourself a jazz artist?

Absolutely. And it’s not thorny at all to me; I can still remember every decision that I made, including one that took place around the time that Dave Sanborn and I made the Double Vision record in the 1980s, and maybe it was even a little before that, when I knew that I couldn’t keep trying to be Bill Evans, or I couldn’t keep trying to be Oscar Peterson, or whoever it was that I was influenced by at that time, because I would always come in second place no matter what. I could spend all day and all night practicing, and I could never be Bill Evans better than he did it.

So somehow or another, I felt that this aspect of jazz that is personal, that you are trying to express your own individualities, the thing that makes you different from somebody else, I felt that that was something that I had to keep striving for, and I did a pretty big shift away from playing swing-based, standard tunes, 32-bar song form—I just kind of moved away from that, because every time I would try to go down that path, I was being an imitator.

It was during that time that I discovered that a few people started to listen to my newer music and said they recognized me—it sounded like me, it didn’t sound like anybody else. And that was really a big deal for me, just that I could stake out my own territory, no matter what it turned out to be. I felt like I was part of that movement of shifting the style of the way I played jazz into a different rhythm base, to a different form, to different ways of structuring my solos. I never veered away from wanting to do it as purely and as good as I have the capability of doing.

You’ve had so many styles and periods in your career, which has now lasted 50 years on record. What are your thoughts about that, having been around for so long and continuing to do what you do?

Well, that’s bittersweet. Of course, I like saying I’m still here, I’m still doing it, I still have fans, I still have people who look forward to come hear me play, and when we meet and greet afterwards and I hear people say that they have all my albums and that they’ve been listening to me for 30, 40, maybe 50 years, it’s a very powerful feeling, and a feeling of responsibility, or love that I can do it, and scariness that I’m playing “September Song,” but maybe I’ve got to be thinking of it as October or November song—you don’t really know.

Do you have any plans to celebrate your 50 years with a special concert or tour of your own at this time?

Do you have any plans to celebrate your 50 years with a special concert or tour of your own at this time?

No, but I’ve got a much better bigger thing that I’m planning for—I’m about to celebrate the fiftieth wedding anniversary with my wife Judy, who has been the reason why I’ve been able to do what I do throughout my whole career, and we are hitting our fiftieth toward the end of September, and right now we still don’t know exactly what we’re going to do, but I’m far more thinking about that than I am about any kind of jazz anniversary.

Congratulations on that, Bob.

Thank you very much. We seem to be becoming more and more in the minority.

That’s a whole other interview right there.

[Laughs] Yes, it is!

Speaking of family, I found this charming video on YouTube in which you’re interviewed by your young granddaughter.

Well, of course you know that you might be on the phone with me for three or four hours if we start talking about Ava.

We can edit it down.

She’s definitely the ray of amazing sunshine in our life. We have a very small family; I have one daughter, Hilary, who is extremely talented, and we’ve collaborated. She’s a wonderful singer-songwriter. We made our record Flesh and Blood together, and we hope that we’ll have the opportunity to do more. But along the way, 11 years ago, came Ava, who’s just a fascinating young talent.

She’s so talented in such an individual way that the rest of us—her mother and father, and my wife Judy and me—we don’t know what to do. We don’t want to send her out to Hollywood and have her get corrupted, or spoil her opportunity to have a normal childhood. We’re just kind of watching and smiling every time she gets straight As, and every time she comes to me having composed music and lyrics to a new song that she sings, [and] that blows my mind that she can do it. I’m just waiting, kind of knowing that she’s going to do something very special in the future, and I don’t know exactly what it’s going to be.

How did that interview come together?

You know, Justin, I don’t actually remember….It may have been related to something there that I’m doing tomorrow, actually. I’m going out to my hometown, a very, very small town in Missouri: Marshall, Missouri, where they have started a jazz festival using my name at the top of the marquee—it’s the Bob James Jazz Festival. This year is its third year, and I believe it was last year when they asked me to do some kind of an interview, and it turned out it was during the time that Ava was visiting us, and I asked her to be the interviewer/moderator, and she rose to the occasion and did her own script and set the thing up, and we had a lot of fun.

Let’s get back to the upcoming live performances with Dave Sanborn. Aside from a midnight gig in Japan, this is the first time that you’ll be playing with each other. Besides the new album, what else might we hear at these shows?

Let’s get back to the upcoming live performances with Dave Sanborn. Aside from a midnight gig in Japan, this is the first time that you’ll be playing with each other. Besides the new album, what else might we hear at these shows?

We’ve just begun our conversations. We are very much in agreement that we should sprinkle in our music of the past, not only the music that we did together with the Double Vision project, but perhaps one or two of the songs that we have been identified with separately from each other individually, and we’re hoping to put a set list together that is a combination of those things. We’re thinking that early in our tour—which certainly, the New York Town Hall thing will be the first one—there’ll be not that many people in the audience maybe that will have become familiar with our new project, which will only have been available for a week or two before that; we know that they’ll feel some comfort in hearing us play stuff from the past.

However, this tour, our whole ambition, our whole motivation and thrust, is going to be with the new music, and we chose very, very carefully what our rhythm section was going to be, and when both of these guys accepted our invitation to be part of this project—Steve Gadd on drums and James Genus on the bass—and then, even more excitingly, they accepted our invitation to join us on the tour to play the music live. We have the opportunity to play this music in acoustic quartet form with the same rhythm section that created it in the studio, and that’s really going to be the thrust of what this tour is all about. Any of the music that we play from the past will be our reinterpretations of those more produced records performed in the acoustic format.

I’m very excited about it; I really can’t wait, because the studio is one kind of process, very meticulous, very much listening over and over and over again, changing, theorizing, debating about what you’re going to do, but eventually you settle on 10 or 11 songs and that’s it—they get mixed, they get mastered, they get delivered to the record company, they get manufactured, and then that part of it’s out of our hands. And what we have in store for us is the opportunity to kind of recreate the music live and see how it feels in front of a live audience.

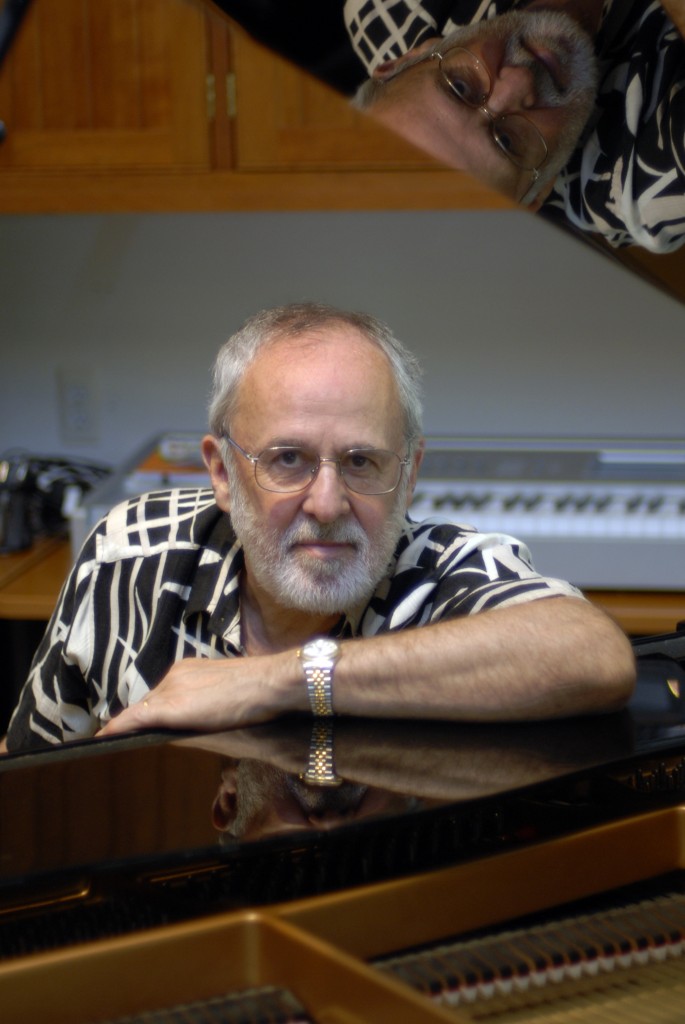

With the new album, were there any particular goals and rules when recording it?

As soon as we decided on the acoustic quartet idea, that made us very clearly into focusing on the sound of our instruments, not enhanced, not sugarcoated in any kind of way—it’s just us playing. I have been associated very, very often with electric piano, with arranging, with various kinds of produced sounds on my other recordings, and this time out Dave encouraged me to just play the piano.

And at first I was a little bit intimidated by that idea, you know. I wanted to call up some of my other stuff; some of my arranging habits or whatever, and I thought, eventually, I felt that he was right, that if we were going to make a new statement, part of it was just going to be just play the music as a quartet and let the sound of our instruments, the sound of the rhythm section, speak for itself, and try to choose the compositions or material that would be strong enough to support that.

It’s just good to hear you playing this kind of straight ahead jazz again. Coming 50 years after Bold Conceptions, it hearkens back to the beginning of your career in some ways.

Thank you very much, I feel that way, too. I never have veered from the feeling that the acoustic piano was my home base, was the thing that I loved the most; that’s what my training was. To this day, I’m only comfortable when I’m sitting at the piano, that’s hopefully tuned beautifully, that hopefully is a great instrument, which is very often a problem on tour, if you have the fortune to have a good instrument to play.

Thank you very much, I feel that way, too. I never have veered from the feeling that the acoustic piano was my home base, was the thing that I loved the most; that’s what my training was. To this day, I’m only comfortable when I’m sitting at the piano, that’s hopefully tuned beautifully, that hopefully is a great instrument, which is very often a problem on tour, if you have the fortune to have a good instrument to play.

And because of that, I have succumbed to the fact that occasionally I have to play synth keyboard, and there are really good ones that make a very good case for sounding exactly like a concert brand acoustic piano, in perfect tune and everything else, but the feeling, the subtlety of touch and dynamics and many, many, many things, it’s just not the same. So that feeling of coming back home and realizing that this piano I’ve got on the stage, it’s a really good instrument, and I have the opportunity to play it in front of an audience, is still very exciting for me.

How did you originally get together with Dave Sanborn?

You know, we should ask each other that question; that’s a fabulous question. I don’t exactly know the answer. I remember, clearly, the years before that, Bruce Lundvall had put Earl Klugh and me together for a collaboration, and neither one of us had specifically thought of it until a producer or a record company person had brought it to our attention and we just did the project. In the case of the encounter with Dave, I’m going to guess that Tommy LiPuma was very involved in that. In my memory of it, Dave would have to clear it up, but in a different way, there was already a kind of team in place that involved Marcus Miller, who had already collaborated with Dave. It involved Al Jarreau, who had already toured with Dave, and all those three guys [had] the same manager who is still with them today, Pat Rains.

I kind of think that they approached me at first more as an arranger or a support person, and somehow [it became] a direct collaboration between the two of us. That’s about as clear as I can be; it’s very foggy how it started up….But the good news for now is that it’s such a more special occasion, and a more vivid way of looking back, to be able to celebrate something that was such a big deal for us so many years ago.

You’ve had a lot of up-and-comers play with you, both on stage and in the studio. Who are you most proud of and why?

Of course Hilary, my daughter, that’s the one I’m most proud of. And having had so many opportunities, it’s kind of impossible to single it out. That kind of question always conjures up the same answer to me, which is the comparison to parents being asked, which is their favorite child?….You can’t really answer that; you’re proud of all of them for different reasons, and some of them need a little more nurturing or love than others. In the case of other musicians I’ve worked with or other albums that I have made of my own, all of which seem like my babies to me, I prefer to let the listeners decided which are their favorites and remain a little bit neutral.

I could go on and on about how important it was that Grover Washington [Jr.] came into my life and that I was very involved in his first records, and he went on to have such an amazing career, and I feel very much a part of that, and I feel that that era had a great influence on my evolution as an arranger and as a solo artist. Going further back into history, certainly the four and a half years that I spent with Sarah Vaughan were like a college education. Learning how to play piano behind one of the greatest jazz singers of all time, and feeling the power of playing for her something that would inspire her and put a smile on her face and make her sing better, I knew I was doing my job. Those things are extremely vivid memories—I love thinking back on them, and they’ve influenced me a lot.

Only two Grammy awards: One with Earl Klugh with the album I made with him, One on One. Certainly those collaborations with Earl are very, very memorable, very important, and I’m very happy that we’re still such close friends and still have fun together. And now, here’s a new opportunity with Dave Sanborn to test the enduring quality of whatever it was that we created in the 1980s with Double Vision to see if we still have something new and fresh to say. That’s a great journey that I’m very happy that we are embarking on.

Something I probably like most about jazz musicians is that they continue to do new things. You’ve always been active and doing lots of different projects. How do you want to be remembered as an artist?

You know, Justin, I don’t even think about it; I think it’s better if I don’t. If I start thinking about that, I become too self-critical, maybe, if I’m thinking about myself in that way. It’s very egotistical, it’s too self-congratulatory; I’m not supposed to be thinking this way. If there is a memory, it will take place naturally, because I’m in a medium that is saved for the future through recordings. And whether it’s an LP or a CD or a direct download on the Internet, that music is out there in space; it’s out there for other people to decide how to remember me, if they do at all. I love having had the opportunity to do it; I hope to keep doing it—it’s a great feeling.

And what you said about the fact that most jazz musicians tend to change and keep looking for something new, because it’s the very most basic thing that our whole music is based on, which is the unknown. When we start to improvise a solo, which is the root of what jazz has always been about for me, is that mystery of having something come into your head, and then just articulate it immediately for the listener or for a fellow musician. An idea that didn’t exist one millisecond ago, and now it happened for whatever reason, and then you just play it. And you improvise, and you deal with what happens in those next moments that follow. That process, I’ll never get tired of it. And when I’m on the stage with other jazz improvisers that I admire, it is so exciting to have that kind of new, exciting fresh dialogue of something that didn’t exist, and then suddenly it happens.