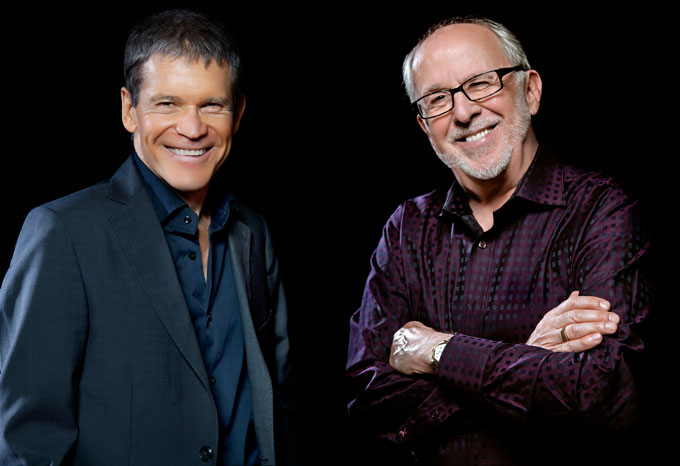

Bob James & David Sanborn on Quartette Humaine:

Bob James & David Sanborn on Quartette Humaine:

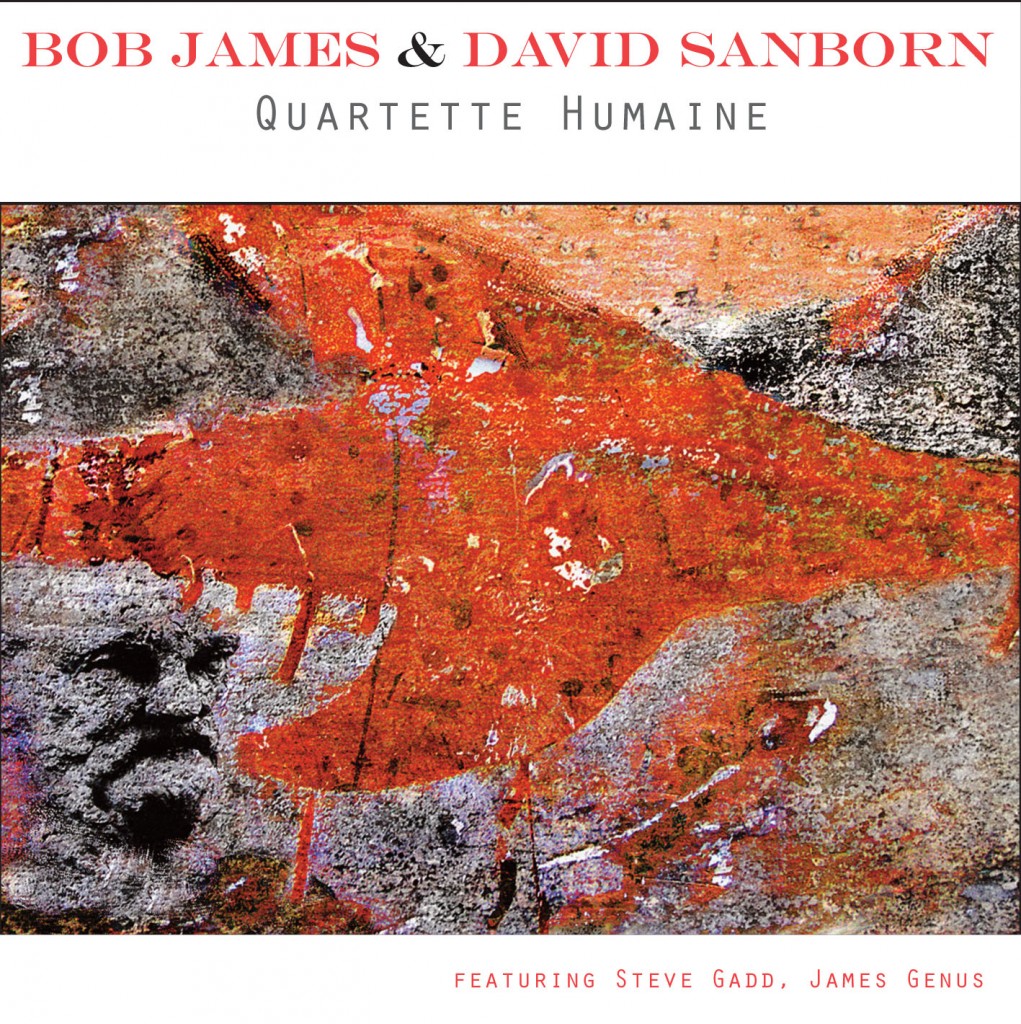

The first creative collaboration between keyboardist-composer-arranger Bob James and alto saxophonist David Sanborn, a quarter century ago, was the million-selling Grammy-winning album Double Vision. Over the ensuing years, the mega-stars not infrequently discussed the notion of a followup. But only now, with the release of Quartette Humaine (their debut release on Sony Classical’s just-reborn OKeh imprint), has that aspiration reached fruition.

“David and I realized long ago that Double Vision had become more successful than we originally imagined it could be,” James says. “Ironically, although we’ve met in the studio, doing other people’s projects, we’ve never toured, or performed together live as a band. The exception was a midnight jam session at the Tokyo Jazz Festival a few years ago. We played just a couple of tunes, but it engendered the feeling that a reunion was way overdue.”

One of those tunes was “Maputo,” the most famous track from Double Vision. “We’d both done it in various iterations with our respective bands, but this was so much fun, so different from those treatments,” Sanborn states. “That was my impetus. I wanted to do something very different than Double Vision, that would be about us just playing.”

After several months of preparation and discussion, Sanborn and James recorded Quartette Humaine in mid-December (2012). On their second go-round, the old masters eschew the pop and R&B production values that mark large chunks of their respective discographies, and offer instead an all-acoustic quartet recital consisting of six new compositions by James, three pieces by Sanborn, and a James-arranged standard. Propelled by legendary drummer Steve Gadd and 21st century bass giant James Genus, the proceedings are reflective, swinging, chock-a-block with unfailingly melodic improvising and beautiful tonalities.

After several months of preparation and discussion, Sanborn and James recorded Quartette Humaine in mid-December (2012). On their second go-round, the old masters eschew the pop and R&B production values that mark large chunks of their respective discographies, and offer instead an all-acoustic quartet recital consisting of six new compositions by James, three pieces by Sanborn, and a James-arranged standard. Propelled by legendary drummer Steve Gadd and 21st century bass giant James Genus, the proceedings are reflective, swinging, chock-a-block with unfailingly melodic improvising and beautiful tonalities.

“We felt it’s far more exciting and adventurous to move forward,” James says. “Times have changed. The music business has changed. We have changed.”

“At this stage of my life, I wanted more than anything to play music that’s challenging and fun, outside the style we’ve been associated with,” Sanborn says. “For various reasons, a lot of my records only reflected one side of the many kinds of music I was doing.” Over the past decade, Sanborn adds, his records “reflect a side of my sensibility that I hadn’t been expressing as much, paying respects to guys like Hank Crawford and David ‘Fathead’ Newman, who inspired me to start when I was a teenager in St. Louis.”

Interestingly, James wasn’t fully sold on the notion of an all-acoustic environment for Quartette Humaine until the project was well underway. “I thought some of the songs might want to be produced, or have overdubs, or maybe strings, or other things associated with our earlier music,” he recalls. “But as it developed, the quartet vibe we created was so strong that it became more interesting to keep it that way.”

It’s a poignant coincidence that the recording sessions occurred a week after the death of the iconic pianist-composer Dave Brubeck, who the protagonists were thinking of as they gestated Quartette Humaine. “We talked about the interplay of Brubeck’s quartet with Paul Desmond,” Sanborn says. “Coming from that, I assumed we’d make a quartet date. I like being able to really hear all the individual instruments. We had this beautiful 9-foot grand piano, and you can hear its sound ring out. You get more sonic purity without all those other elements.”

Indeed, both the tunes and treatments channel Brubeck’s gift for creating communicative music from highbrow raw materials. “Dave has a similar capability to Paul Desmond—though in a different way—in that the lyric quality of the way they play takes it into an emotional-romantic concept rather than an intellectual one,” James says of Sanborn. “I felt—and I still do when I listen to the Brubeck quartet—that they were taking us on an adventure, and some of the adventure was challenging. Just when you thought you knew where you were going, they’d go somewhere different.”

That “edge of being in an unknown place” permeates “Mondo Rondo,” on which James signifies on Brubeck’s 9/8 classic “Blue Rondo A La Turk” by creating “a fast, virtuoso tune on which we take the listener through a bunch of odd time signatures where they may not always know where they are.” He adds, “Steve Gadd flowed through it so effortlessly that I got worried it was sounding too smooth.” Another new opus, “Better Not Go To College,” reimagines Brubeck’s classic “In Your Own Sweet Way” “in mood though not exactly in style,” and references Brubeck’s breakthrough album Jazz Goes To College, which James recalls hearing as a high school sophomore in Marshall, Missouri.

Sanborn’s ravishing tone comes to the fore on James’ arrangement of “Geste Humaine,” composed by the French songwriter-singer Alice Soyer. On the American Songbook classic “My Old Flame,” addressed in 12/8, the altoist soars soulfully on the cushion of James’ elegant voicings and written thematic counterpoint bassline. He uncorks an ascendent declamation on “Montezuma,” which James composed “very specifically” for his partner. “I thought about supporting Dave’s sound with a symphony orchestra,” James laughs, describing the latter piece. “There’s dramatic tension that resolves in a very major, majestic way, with Dave way up in his upper register. But we realized that interpreting it in the raw quartet mode was even more powerful.”

The alto master presents his gift for melodic invention on his three compositions, offering a new ballad, “Genevieve,” for his granddaughter, and revisiting two tunes that Gil Goldstein framed with elegant orchestrations on the 2004 classic, Closer—“Sofia,” a ballad for his wife, and “Another Time, Another Place,” dedicated to Herbie Hancock.

The alto master presents his gift for melodic invention on his three compositions, offering a new ballad, “Genevieve,” for his granddaughter, and revisiting two tunes that Gil Goldstein framed with elegant orchestrations on the 2004 classic, Closer—“Sofia,” a ballad for his wife, and “Another Time, Another Place,” dedicated to Herbie Hancock.

“It’s so much fun to do it this way,” Sanborn says. “I used to separate live playing from being in the studio, and got into a mindset of having to labor over a record and make it right. I want the studio to reflect that live experience—the fun of discovery, not knowing what’s going to happen until it happens.”

By following such in-the-moment dictates throughout Quartette Humaine, James and Sanborn have produced another masterpiece. As James sums up: “We seem to be reflecting back on what our lives have been, where our earlier projects have taken us. We tried to figure out the strengths we’ve learned by experience, and to bring them to this project where we celebrate that we’ve done so many things and that we’re still able to keep creating.”