We’ve been talking about jazz this whole time, but to the younger generation you’re mostly known as someone whose work has been sampled in countless hip-hop songs.

We’ve been talking about jazz this whole time, but to the younger generation you’re mostly known as someone whose work has been sampled in countless hip-hop songs.

[Pauses] Is that a question? [Laughs]

On first glance, you’re probably the last person in the world that would be associated with hip-hop, as indelible as the melodies and the compositions that you’ve come up with are. Do you have any idea how it all started? I’m guessing it was from “Nautilus,” but when did you first realize that something was going on there?

I wish I knew. I was flabbergasted, and I think I was probably a little bit slow in even finding out about that crazy phenomenon that happened. The first one that I discovered came about as a result of a friend calling me to ask me if I was aware of [DJ] Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince, and they had a recording [“Here We Go Again”] in which they had sampled my recording of “Westchester Lady.” This came before, whether or not historically it came before the sampling of “Nautilus,” I don’t know, but this was the first one that I became aware of. And it reached the public spotlight because their record [“Parents Just Don’t Understand”] won the [Grammy Award for Best Rap Performance].

So I was sort of confronted with it, and shocked, angry, confused, all those kind of feelings. Because when I listened to it, all they did really was they just took my recording and they played it from beginning to end and they rapped over it and they called it their own recording. And I didn’t understand what that meant in terms of the copyright, because they hadn’t come to me for a license or anything; they just did it. And many times during that time period, the same kind of thing happened, where a lot of the rappers, or a lot of rap producers, either didn’t care, or they were so naïve that they didn’t even realize that there was such a thing as a copyright and that they had to get permission.

So all of those things were very complicated, and trying to get to the bottom to of it and protect my copyrights. I didn’t ask them to do it, I didn’t necessarily want somebody rapping over or playing trumpet over or anything else over my own recording; I thought it was okay the way it was. At least I would have wanted to hear it before I gave permission. So from that time over the last 25 to 30 years, it’s been an ongoing—I guess you would call it an adventure—to both protect my copyright, but also to appreciate the fact that the young people who are hearing my music, albeit distorted in this instance, at least they were hearing it in a way where if they knew it was me and if they were intrigued by it, maybe they would explore the music the way I originally intended it to be. It’s been a very interesting ride; I’ve tried to be respectful of other artists and how they do things, while at the same time protect my own integrity.

These days, whenever these samples are used, the original composer is credited. Is this something that was resolved on your end?

I like to think that I was one of the people that stood up for my rights and helped refine the whole process of licensing sampling—defining it, what is it, and how do you define it, how do you pay for it, how do you deal with the fact that they want to use just a small chunk of your music and change it. In some ways, every instance was different, but the fundamental thing was, to me, I feel, the big, big, big beneficiary of music copyrights having been set up and refined in the early twentieth century, and all across creative people, composers, whatever, who have a chance to own our music, whether it be owning our recordings or owning our compositions, and owning the publishing of them or keeping control of it, is the most powerful thing that we have as professions.

And the hard work and sometimes the extremely problematic process of establishing a way that even nightclub users pay for the use of live music or recorded music in any place that’s being operated for profit is a very, very complicated thing. I’m not getting rich out of the way the George Gershwin estate is, etc, etc. etc., but all of us who create new music are the beneficiaries that carrying the torch for the future can make sure that we’re protected.

You can go on YouTube, and in the comments section for one of your songs you can see what other hip-hop songs these melodies are contained in.

It’s humbling to know that so many of those people, they’re kind of aware of it. They’re aware of the bells on “Take Me to the Mardi Gras”….If they think of my name at all, they think of me as somebody from the olden days, from way back in ancient history, with cobwebs all over my tombstone, you know? They’re shocked if I’m still alive and I’m still making my own music.

To your credit, Bob, you’ve never tried to do something like tour with these artists or stick your neck out there as a person who’s associated with all this.

In a sense, I’m very flattered that my music reached them in a way that had that much of an effect. I have had some opportunities to meet with some young people who are rap and hip-hop fans that I’ve had some very good conversations with, and I think some of them have gone on to listen to the other parts of my music—I’m happy for that. But I certainly didn’t change my path in any way for what was the most important thing to me, which is to remain true to what I have passion and art for.

A lot of your stuff with CTI [Records] toward the beginning almost veered toward filmic orchestral work. Can you talk about how that evolution came together?

A lot of your stuff with CTI [Records] toward the beginning almost veered toward filmic orchestral work. Can you talk about how that evolution came together?

By that time I was doing a lot of studio work as an arranger, maybe more than as a jazz solo pianist. I wasn’t touring that much, and Creed Taylor gave me the opportunity to record my own solo projects, but the bulk of what I was doing with CTI then was still arranging for other people Stanley Turrentine and Hubert Laws and Grover Washington. It was a very powerful period of time for me in so many ways, because part of my thought process was, should I be concentrating more on being a pianist, or should I concentrate more on being an arranger, because I felt like I might be becoming just a jack of all trades, which would be a problem.

And again, I had to go to my best source of inspiration, my wife Judy, who eventually advised me to just be myself; that I was a combination of all those things, that there’s no reason why I needed to apologize for the fact that I was an arranger and a pianist, and to do everything. So I just stopped worrying about that and let whatever came naturally, whatever my opportunities would turn out to be, try to respond to them all, and I think that has happened to me to this day. I still feel myself as a combination composer-arranger-pianist, more than just a pianist who occasionally writes a song or whatever.

Had you ever received offers to score motion pictures at that time?

Just one or two. I was asked to score the picture Serpico, which became kind of important to me because I had a chance to work with Sidney Lumet, a big director. It led to a number of other things, but at the same time I was actually trying to steer myself away from that part of the business and become more of a jazz person. I was good at doing studio work, doing TV commercials, those kinds of things, but they were not very rewarding to me musically.

And even the film scoring, I wasn’t out living in Hollywood, I hadn’t committed myself to it, I felt that most of the opportunities that I would have at that time were more rudimentary—just a job, rather than the opportunity to really create something of significance of my own. And that pressure of a producer or a director or somebody telling me that they wanted me to make music in a particular kind of way felt restricting to me. And so I was trying to break away from that, frankly, at that time, and just make more of a commitment to either playing or arranging music that exists on its own merits, and not behind as a movie score or a TV score.

Can you talk a little about the origin of the song “Westchester Lady”?

Well, here we go again with Judy. I was living in Westchester County at the time, this was 1976. I don’t know why we ended up calling it that; I don’t even remember whether Judy came up with that title or not. But she came up with many of my titles—doing instrumental music, I would usually prepare them without any title on them. I would come in with “song number 35” or whatever it is, and at the very last minute, some title would suggest itself to us. I kind of don’t remember, other than the fact that she was my Westchester Lady, and I’m happy that that song became the success that it did. In some way, it’s another kind of tribute, celebration of our life together.

There’s a little story about that recording: I had this idea of having a little vocal hook added; we recorded the instrumental track and I had Harvey Mason on drums. I was working with Gary King at that time on bass but he was sick, so Will Lee came in and played bass, and has to this day told me that if I had used him more often I would have had more hits…

But Creed thought the record was finished, but he reluctantly agreed to let me do the vocal session and I brought in these singers, one of whom was Luther Vandross, who at that time had not started his solo career; he was kind of successful as a background studio singer in New York. And we did this little vocal hook thing, and Creed didn’t like it and even I had to agree with him in the end that it didn’t quite come off, and we never put it on the record. Years later, I had this chance to work with Luther, and he remembered it and he reminded me and [said] to me that had I used his vocal on it, it could have been a really big hit after that. But you never know.

I didn’t know about that.

It was so obscure that I can now no longer find those original tracks. I’ve been looking at Iron Mountain, which is the vault where all old recordings are stored, and I’ve desperately tried to come up with the original basic multi-tracks that would have had Luther’s vocal on it. It also had Patti Austin on it; same session. And I would have loved to have done a reissue with the alternate version, but we haven’t been able to find it. And maybe it’s been erased or deleted or who knows. I don’t know where it is.

Back in those days, you had very interesting choices in cover tunes that you selected on those records. Was there any kind of method you had in picking them?

Back in those days, you had very interesting choices in cover tunes that you selected on those records. Was there any kind of method you had in picking them?

I guess I have to give Creed Taylor the credit for being very specific about understanding that jazz fans like to listen to jazz artists reinterpret a very well known theme that they already know in another format. He was very much interested in taking classical themes and then reinterpreting them in a jazz way, and sometimes one of his staff arrangers was called upon to do that many, many times. And in his way of producing records, there was always a combination of having new, original things, but that also an interpretation of very familiar standards or reinterpretations of classic themes.

The most significant one for me was my first record for CTI in which I recorded the song “Feel Like Making Love.” And it had a history, because I had been hired to be the piano player on Roberta Flack’s recording session in which she premiered that song and I heard it for the first time in the studio recording with her, and Gene McDaniels, who was the composer of that song, and was also the producer of that session. And it was one of those times when the song was so amazing and the hook was so strong, and I just knew that it was going to be a hit. And coincidentally, it happened at the same time when Creed had given me the opportunity to do a solo record.

So I of course said that I wanted to record the instrumental version, and hopefully the timing would have been good for me to cover the first instrumental version of that song. And mostly, coincidentally, I ended up with the same rhythm section that had played on Roberta’s record. It was Gary King on bass and Idris Muhammad on drums. Richie Resnicoff on guitar, Ralph MacDonald on percussion. And we recorded it in the same key and kind of the same tempo, so it definitely had a very similar feel to Roberta’s record, and mine got finished much quicker than Roberta finished her album. So my instrumental version actually came out before hers did, and she was not happy about it, because she wanted an exclusive on the song.

It was not intentional; it was just that she took a lot longer. And we eventually made up and we’re friends, because quite obviously, my instrumental version did not hurt the amazing success of her version, and I kind of rode on her coattails and radio stations played both of our versions back to back. I think it turned out to be really very good for both of us. It got my solo career off to a really big start.

I also have to express my appreciation for the bass on “Take Me to the Mardi Gras.” How did you get such a rich sound on that?

Well, it was a follow-up. It came a year after I had done the album that had “Feel Like Making Love” on it, so we were basically trying to go down a similar path—take a recognizable song and reinterpret it. Again, I had Ralph MacDonald on percussion, and he created that cowbell rhythm pattern that ended up being so charismatic and so identifiable in the hip-hop world. But we weren’t thinking too much beyond that; I’d love to say that I had some great concept about it, but it was just another tune on the session, and we had no idea what kind of path that recording would take. Certainly, we didn’t anticipate anything like the rap/hip-hop generation coming along 20 years later.

Something you were also really identifiable with was the fact that you used numbers for each album title for a really long time. What made you decide to keep going and going?

Again, that was Creed’s idea. He was a believer that if you numbered the titles of your records, it gave your fans a chronology. So that if they didn’t become fans until your sixth album, that they liked that sixth album, and then they realized that it’s a number series, they knew exactly how many they had to go back in time. So it was a very specific thing. And the more records you made, I got to my twelfth record, and the fans said, “Ooh, I guess I’ve got eleven more records that I need to search out.” I didn’t want to just exactly do it the way Creed did it, because we just did numbers on it with the four records I did with him.

When I switched over to Columbia, I changed the titles and made an indirect reference to numbers. And I called my first record for Columbia Heads, which was a nickel representing five, and then my sixth record was Touchdown, six points, and so on and so forth. And finally, I kind of dropped that concept after the twelfth record, and in some ways I wish I had kept it going. By the twenty-sixth or twenty-seventh record, it would have had a whole different kind of fun attached to it.

It worked for Chicago.

It sure did. I’m sure Creed probably stole it from Chicago; that was already in place when we did ours.

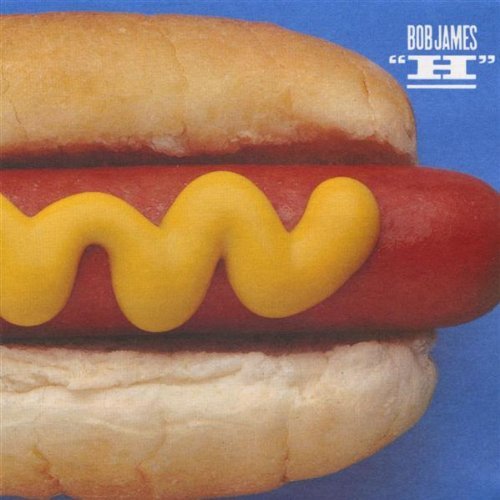

The album H is one my favorites of yours. Is there any story behind that besides the fact that it sounds like the number eight?

The album H is one my favorites of yours. Is there any story behind that besides the fact that it sounds like the number eight?

It’s the eighth letter of the alphabet. It was a kind of an obscure deal, and we had a hot dog on the cover, “H”—we were definitely trying to be obscure at that time. Once again, Judy is represented on the inside cover of H; we’re standing there at the hot dog stand in New York City ordering a hot dog from one of the vendors. My daughter Hilary is there, and the hot dog vendor happened to be Joe Jorgensen, my engineer at that time, who took on the role of hot dog vendor for the photo session.

I think in those liner notes you mention that eating a hot dog was inspiring an upcoming tune of yours. Do you remember which one that was?

I can’t even believe that you’ve done your homework that well.

I happened to see this just recently when I was browsing at Colony!

Nevertheless, I’m very impressed, and you jogged my memory. I do remember saying that; that it was just one of those things that you say because you have to say something. But I doubt that I actually was inspired by anything specific which came a year later—that would have been the Sign of the Times record, which wasn’t even on the drawing boards at that time.

Any reason why the All Around the Town live album was released something close to two years after those tracks were originally recorded?

Gee, I wasn’t even aware that there was that much of a gap. It took quite a bit of time to put it together and get the concept of it. You know, Justin, I actually don’t remember. One of the things that I now remember, which is very poignant, is that one of those performances was at Town Hall, where we’re going to be performing with [David] Sanborn in June, and I’ve only performed there a few times since that time, but that Town Hall concert was extremely memorable for me, because it was the unique opportunity to have three pianos on stage where I was playing along with Richard Tee and Joanne Brackeen, with Steve Gadd and Eddie Gomez as our rhythm section, so that was a really great, fun time.

Continuing on H, “The Walkman.” Love that song. Was that inspired by the product itself or you hearing about it?

It was the timing. I’ve always been a gadget lover; I’ve always tried to keep up with the latest stuff in terms of portable ways of listening to music. And I had one, and most all of my buddies had one at the time. And I was a little bit thinking that maybe I might end up getting some kind of a nice endorsement from Sony by calling my song that. Didn’t happen, but I guess it didn’t hurt to give that a shot. I always liked that song because it did have that feeling of walking down the street listening to headphones.

In the beginning part, is that a drum machine that’s being used for that propulsive beat?

Great question; don’t know the answer. I have to go back and listen to it again. If it was a drum machine, it was pretty primitive at that time. I can sort of remember some of those drum machines that we occasionally used, and some of them were not even particularly subtle touch sensitive, they were just very robot-like…every note, same velocity, that kind of thing. I won’t say that I was above using them, but I actually don’t remember.

I love the piano sound on that whole album, as well. Does that strike you as a particularly well-recorded piano for that?

It was the era of Joe Jorgensen—great, great engineer. I’ve been pretty lucky throughout my career, and I’ve tried to cultivate a real, real close relationship with the engineer, specifically with the sound of the piano. I started having the great opportunity to work with Rudy Van Gelder, who was really one of the masters of that era, and I went from him to Joe Jorgensen to the years that I was at Columbia and made a lot of records with Joe. After that, I have since then developed an even closer, longer relationship with Ken Freeman, who knows the piano sound so much that I don’t even think about it anymore; I don’t even know the names of the mikes that he uses, but he hooks me up, and we have a shorthand language of communication that’s pretty great. He was the engineer of this new project with Dave Sanborn also, and very specifically a part of that piano sound.

Final question about that album: I notice the song “Thoroughbred” tends to show up in a lot of best of Bob James compilations. Do you have a soft spot for that particular tune?

Another Judy title—that’s the first thing I remember about that; goes back too far in history. Another example of how the piece was instrumental, thought of as abstract, and then somehow it conjured up something to somebody, probably Judy in this case, that made her think of a racehorse. I don’t remember the derivation of it beyond that.

It’s a very cinematic tune. Shortly after “The Walkman” you did “Sparkling New York” for Suntory Whisky, right?

It’s a very cinematic tune. Shortly after “The Walkman” you did “Sparkling New York” for Suntory Whisky, right?

Yes. And that definitely was one that I got paid for a sponsorship for Suntory Whisky. It was a direct result of being commissioned to do that piece.

Kind of a sweet payback.

Yeah, and I guess it was also the beginning of what has become a kind of a love affair with Japan. They’ve been great fans, great supporters of my music. In the years since, I’ve toured there so many times, and still it’s one of my very favorite places to play, because I think they do their homework and they appreciate the effort that we put into our music, and I feel really lucky to have that fanbase over there.

I saw that documentary of yours about visiting the places in Japan devastated by the earthquake and tsunami…

Very lucky to have been able to do that and to give something back. I made some very, very close friends as a result of that. I always think about how can I give something back, and that was a great opportunity.

Was the song “Marco Polo” also a result of a commission for the commercial it was used for in Japan?

It was a song that already existed and not commissioned. It had been a favorite of the Japanese audience, which brought a big smile to my face because I wouldn’t have thought of it otherwise. I don’t think that that song had any impact, particularly in the U.S., but it had great success over there in Japan for whatever the reason was, and they always ask me to play it every time I go over there.

When I first heard that song, I thought it was something you might hear on a Japanese morning show or in a mall. It has that gentle quality to it.

It might have been used for that, for all I know.

Regarding your success in Japan, I know you’ve been big there since “Angela (Theme from Taxi)”—I guess we couldn’t do this interview without mentioning it at least once.

Taxi came about as a little bit of a fluke. I didn’t solicit work in the TV theme business; they came to me as a result of my record [BJ]4…the producers of that show had a copy of that in their collection and they started playing it during rough cuts, and so they liked the mood. They approached me with the idea of doing new, similar music. On one of the sessions I attempted to do that; I composed this song which I originally thought was only going to be a piece of background music, and they liked it so much that they asked me if they could use it as the main theme. So it happened a little bit as very much of a fluke, positive thing, and I’m so happy to have that history with that song still being asked for all the time by my fans.

How exactly did you get so big in Japan then? I’m guessing that Taxi wasn’t as big there on the airwaves there as it was in the States at the time.

I don’t really know, but certainly I’m asked to play it as much or more over there than I am in the U.S., and actually I don’t know the history of the TV series, whether it got translated into Japanese and became popular over there or not.

Well, the word for taxi in Japanese is “takushii”…

Yeah, “takushii.” [Laughs]

When you have a song like an “Angela” on an influential show like that, is it safe to say you’ll be collecting royalty checks for the rest of your life?

It hasn’t hurt. I would say that it’s up there at the top of my ASCAP statement, for sure. I’m very, very lucky.

It must get played somewhere in the world at least once a day. It’s an incredible thing to be a part of, I guess.

And that’s why I like just going in and doing what I do, because you never know how those things are going to turn out, you know. And sometimes the things that are the most successful are the things that you never anticipated at all. And if you try to do something on the theory that, okay, I should be doing this because it might be very commercial; I’m probably making the wrong decision, anyway.

Just one more for you about Tappan Zee: I thought it was really incredible that you had an association with Columbia Records where it read Tappan Zee on the label in every part of the world. How did you get that kind of autonomy?

It was a very short period of time, about three years. I had a great manager—when I left CTI, my manager also happened to be the manager for Paul Simon, and so he wielded quite a bit of power for Paul Simon at the time. My vision of it is when he was negotiating my deal, it was way down at the bottom of the agenda when he was trying to negotiate the big stuff for Paul Simon, and they probably just said, “Yeah, okay, we’ll give you Bob James, blah blah blah blah blah,” [laughs] but they may be tougher with the Paul Simon part.

He did carve out a deal for me to have my own separate custom label in which they wanted me to be possibly a different version of Creed Taylor, where I would handpick artists, not in any kind of big way, and it seemed like a good idea at that time, but frankly, over that three years I discovered that I much preferred being a musician to being a businessman. And I kept the name as a kind of a custom production company logo, but gave up the idea of trying to make it into a full-fledged record label a long time ago, and with no regrets.

I’ve watched the spectacular, in many ways, success of GRP [Records], which started almost at the same time, and Dave Grusin had a really great business partner in Larry Rosen, and they carved out a much different, bigger version of having a custom label and staying with it. Sometimes I wonder what might have happened if I had stayed with it then. I didn’t really want it; I don’t have any regrets about that, and I still am happy about the fact that there was enough of the history with our recordings that we made. And since I still own the name Tappan Zee, we could reactivate and do something more ambitious at any time. Who knows?

In those three years, the other artists were recording on the label as well as yourself?

Yes. I had Richard Tee, who made a record for me, Steve Khan, Mark Colby, Wilbert Longmire. I was just beginning to get my feet wet, trying to figure out who the people were that I could give something special to, and at the same time I knew I had to really devote too much time to the business end of it, and in many ways I didn’t even like the responsibility of having other artists’ careers dependent upon my business decisions.

That’s all I’ve got, Bob. Thank you for today. Do you have any other messages for your fans around the world and the ones who will be seeing you on tour this year?

No, I think you’ve just about covered my whole life. I really enjoyed talking with you and have a great appreciation for the fact that you did so much homework. I appreciate that a lot. I’ve enjoyed going down memory lane with you.