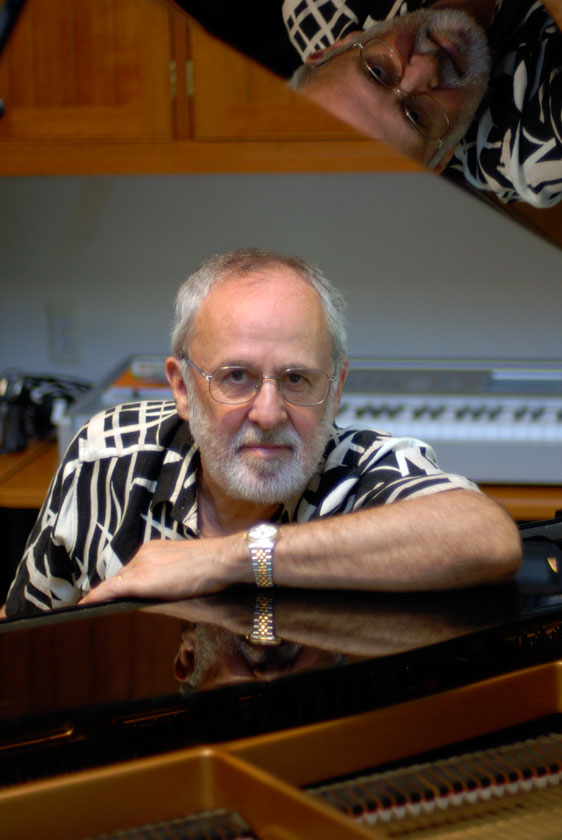

“I’m flattered to be a part of hip-hop’s history,” says Bob James nonchalantly. “But I believe we’re still at the beginning of understanding how young people make music.”

“I’m flattered to be a part of hip-hop’s history,” says Bob James nonchalantly. “But I believe we’re still at the beginning of understanding how young people make music.”

Bob James’s career developed during a time when radio ruled, records sold, and Roberta Flack had the country’s number one song. Things were different then. Popular music was changing, and over in New York, kids were priming themselves for a burgeoning hip-hop scene. James was thirty-five by 1974 and had just released his first solo album on CTI Records. His subsequent projects for the label were both commercially successful LPs and unsung flops. Regardless of units sold, it was those very records that would lay the foundational sound for some of hip-hop’s most coveted records. It was those kids in New York who initially took James’s music and adapted it for themselves to use and the world to see.

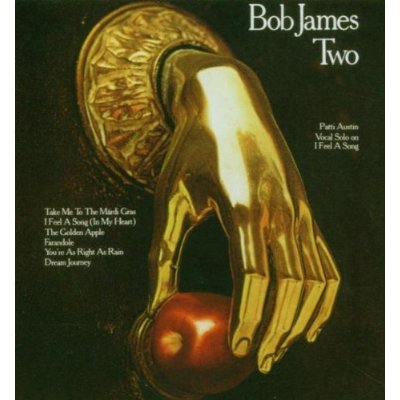

James’s first three CTI releases—One, Two, and Three—are amongst the most sampled records ever. And if we’re truly beginning to grasp how younger generations make music, it’s safe to assume that James’s catalogue is a resource that’ll be continually sifted through and sampled from.

In this three-part interview, he talks in-depth regarding details of his career: The first part of the interview touches on colorful names that are intermingled with his history, its development and legacy. Next, he reflects back on his first three CTI releases, breaking down the most sampled songs on each album. In the interview’s final component, Bob James explains the process of sample requests throughout the years, its affect on him, and why he’s “flattered to be a part of hip-hop’s history.”

I. Quincy, Creed, and the Biz:

What role did Quincy Jones have in developing your career?

Everyone talks about the history of our field and Quincy Jones has a lot to do with my history. You could even say he discovered me. He was very influential at several key stages in my career. He was a judge at a jazz competition that I did when I was still in college, and my group ended up winning the whole thing. Quincy then signed me to do a record called Bold Conceptions in the ’60s. That, of course, was very important to me. Ten years later when I moved to New York, I met Quincy again, and it was Quincy that introduced me to Creed Taylor. This launched my career with CTI. Those two things are extremely important to me, and how my career played out. Quincy was definitely pivotal.

Everyone talks about the history of our field and Quincy Jones has a lot to do with my history. You could even say he discovered me. He was very influential at several key stages in my career. He was a judge at a jazz competition that I did when I was still in college, and my group ended up winning the whole thing. Quincy then signed me to do a record called Bold Conceptions in the ’60s. That, of course, was very important to me. Ten years later when I moved to New York, I met Quincy again, and it was Quincy that introduced me to Creed Taylor. This launched my career with CTI. Those two things are extremely important to me, and how my career played out. Quincy was definitely pivotal.

You were with CTI for a few years before your own project debuted. When did Creed Taylor interject and aid in the progression of things?

Well, I was working a lot with Creed at the time for CTI. But I was working primarily as an arranger and would play piano on other jazz artists’ records. After doing this for about two or three years, on a fairly stable basis, and being on the support staff for other artists like Grover Washington, finally Creed asked me if I wanted to do my own album. So of course I said yes. One ended up being my first for CTI.

What specifically was Creed Taylor’s influence during those years? Is there anyone else you’d credit in aiding your career?

What specifically was Creed Taylor’s influence during those years? Is there anyone else you’d credit in aiding your career?

Well, Creed’s whole outlook on production was very influential to me. He always believed in hiring the best musicians possible and he put a lot of emphasis into the mixing and production value. He always used a fantastic engineer named Rudy Van Gelder. I can say that Rudy was very important in my development also. He cared about the way things sounded more than any engineer I’ve worked with. He also had a very identifiable sound. I’ve never thought that much about the recording process, just the composing and playing. But together, Rudy and Creed had a definite personality in all their projects. The combination of Creed’s ears, how he listened to things, combined with Rudy’s engineering style made them a great production combo. I’d always try to keep that same feeling going into my works for many, many years after first working with Rudy and Creed.

Strangely enough. Biz Markie is another name that’s attached to your legacy. He claims to have a 12-inch of “Take Me to Mardi Gras.” Can you confirm or deny this once and for all?

I couldn’t really tell you one way or the other. [laughs] It’s definitely possible that a 12-inch of “Take Me to Mardi Gras” exists. I wasn’t personally involved in making the 12-inch edits. Often times, it was made by the engineer. I assume some of these versions are legit and some aren’t. I’ve never physically seen any or heard other versions besides what’s on my LP.

Well, adding to the rumor, Biz says his version doesn’t contain the bells at the beginning.

That intro with the bells sticks out in the front of the arrangement, so I’m sure it would be possible to take chunks and make edits. What I think is very doubtful is that anybody did. Someone would’ve had to go into the masters, and the multitrack tape, and manually take the bells out—or any other individual elements for that matter. There’s a small window of opportunity that an engineer during the time could have taken out the bells after our recording session. But I wouldn’t know why someone would do that. Especially if it was a promotional 12-inch for the LP. The possibility of a 12-inch single could certainly exist. But a version without the bells seems unlikely to me.

That intro with the bells sticks out in the front of the arrangement, so I’m sure it would be possible to take chunks and make edits. What I think is very doubtful is that anybody did. Someone would’ve had to go into the masters, and the multitrack tape, and manually take the bells out—or any other individual elements for that matter. There’s a small window of opportunity that an engineer during the time could have taken out the bells after our recording session. But I wouldn’t know why someone would do that. Especially if it was a promotional 12-inch for the LP. The possibility of a 12-inch single could certainly exist. But a version without the bells seems unlikely to me.

II. Three, Two, One: Revisited

Three (CTI) 1976:

I was three years into a solo recording career with CTI at the time, and things were going good. The first two records sold well and I felt like my career was really solid by this time. But I wasn’t really sure where I was headed on this album. Once again, I had no idea of what would become of anything I made. Especially having been in the instrumental jazz field for a while at this point, I was wondering what else I could do. The meat of this album is in the parts where a lot of improvising took place. But with this, I didn’t know what was going to stick with the public. As a musician, improvisation is great; but the public doesn’t care, they just want good tunes. [laughs] This album has some of my favorite moments, but as far as the public was concerned, I think it fell a bit short of what I would’ve liked. And with “Westchester Lady,” it wasn’t until years later that people even wanted it hear it on the radio. This album remains a sentimental one because of the time it was recorded. The music industry was going through a lot of changes. This didn’t sell as well as the two previous LPs, but I’m still proud of it. There’s a certain element of randomness to this LP, which I like.

Track #3: “Westchester Lady”

The tune, the hook, and main melody of this one was just a jumping point for improvisation. At this point I was really into trying new things and improvising almost wildly at points. I mean, of course improvising has always been an important part of my compositions, but I felt like I now truly had the freedom to do whatever I wanted. I was always looking for schematic material to get a song started, and this song did take a while. But I was real happy with the results when we finished this one because it took longer than some other songs we had done by then. For me, “Westchester Lady” is a real signature piece. I love this song.

This is probably the most sampled song on this album. People sampled “Westchester Lady” too, but this album as a whole isn’t as heavily sampled as One or Two. I’m not sure why, because it seems like this album has a lot of the same qualities as my other stuff, which get sample requests all the time. Nothing was really different about the attitude we had coming in to this particular song though. We just went in looking for a hook and a groove, and I think the fact that we found such a solid groove indicates to me that we did our job right on this song. I think that’s what held up about the song and that’s why people sample it. The groove is very solid on this one.

Two (CTI) 1975:

Thinking back on it, this album is like my sophomore year as a recording artist. By the time we went into the studio to cut the album, One was already pretty popular, so we needed a strong follow-up. There are several songs on this record that were continuations of the same concepts as the first one. There was an adaptation of a classical piece on it called “Farandole,” which went on and got a lot of airplay. The other track was “You’re Right as Rain,” which was my arrangement of a popular vocal track at the time. We tried to give a groove to it, similar to “Feel Like Making Love.” This record reminds me of my friend Ralph Macdonald a lot too because Ralph really helped me out. He helped out all the rappers too by playing the cowbell part on “Take Me to Mardi Gras.” [laughs] Ralph has had a lot of success from his records that have been heavily sampled too. And one of his most successful samples is from a tune called “Mr. Magic,” that Grover Washington did. The part from “Mr. Magic” that got used was the arrangement I did for it. But because I didn’t technically write the song, Ralph got all the income from that track. [laughs] I did the arrangement and played piano, but I didn’t see any money from “Mr. Magic.” We talked about it years later and still joke that we’re even, because he never saw any income from playing the “Take Me to Mardi Gras” bells. [laughs]

Track #1: “Take Me to Mardi Gras”

I was a pretty big fan of Paul Simon at that time and even did some work with him in the studio. I’ve always really liked that song and thought I could bring something to it as an instrumental version. So I decided to do it with a kind of Latin groove, and low and behold, twenty-five years or so later, these hip-hop guys used it a lot. I mean it’s a really simple vamp. Ralph [MacDonald] is the guy playing the cowbell on the intro. Ralph played percussion on many recordings in the same era as I did. And he’d played percussion on many of my albums, while I played piano on many of his. So he helped me out this time by sitting in and playing a pretty standard intro section. It wasn’t anything that was really thought about or heavily planned. We were just improvising in the studio and trying to establish a carnival type of mood before the melody came in. We wanted to just let the rhythm section do their thing. But the way the record got mixed, the cowbell part is really prominent. I’m sure lots of rappers were just looking for a loop to rap over and the tempo for it was just right. That’s why I think Run-DMC and other early folks used it so much. I am very fond of this song.

Track #4: “Farandole (L’Arlesienne Suite #2)”

The way we worked with rhythm in that era were often repetitive vamps. There were some real nice bassline vamps that were similar to “Nautilus.” They were short and just two measures long that just repeated, so it is very easy to edit. I think this has been sampled many times because there is a big enough chunk separated from other elements, which made it easy for producers to come in and make a loop out of. It is a classical composition by a composer by the name of Bizet, and I just arranged it and adapted it for a jazz tune. Creed and I liked playing around with compositions.

One (CTI) 1974:

This is the most sentimental project of mine. I’m amazed at the life it still has even though it was recorded thirty years ago. The music business surprises me in all kinds of ways and this has been one of them. The most rewarding thing about this project, which I was committed to and worked so hard on, is that it took on new life years later. It’s amazing really. Given all of that, I never would have anticipated how so many songs from this record would end up in a completely different genre. When I recorded the album, I wasn’t thinking about it in that way. In the back of my mind, I was thinking that this album, at the very least, would give me a chance to record some arrangements that I could use as a demo. [laughs] I wasn’t even thinking about it as a full time solo thing. And that’s why the album is so eclectic. I did all kinds of stuff, used different musicians and orchestras just to have a wide variety of music to show people. One song in particular, “Feel Like Making Love” was also done by Roberta Flack around the same time. Roberta’s version became a huge hit, so I sort of rode on the coattails of that. [laughs] Radio stations at the time would play both our versions back to back, which gave me a lot of exposure. I think Roberta Flack’s success helped catapult my record sales. “Night on Bald Mountain” was another cut that got a lot of airplay. I think those two songs helped make the album a success. I had no idea the record would become commercially successful, so well remembered and so sampled.

Track #1: “Valley of the Shadows”

Well this is the type of tune that would be difficult to convince record companies to do in the later years. But at the time, Creed [Taylor] was very open to letting me do what I wanted to do. I really loved having the chance to do something like this. In a way, I treated this song like a film score because it was very dramatic. And, I suppose that in the back of my mind, I was hoping this song would help me get work in the film-scoring business. Although I can’t trace my film work to this song, I think it did indirectly help me get future jobs in films. I definitely had a lot of offers to score movies after it was released. I think people realized my background allowed me to do that type of music too. It was full of contrasts and was just really different. That song was probably the most radical and daring in that era because it was very different than what anyone else was doing.

Track #4: “Night on Bald Mountain”

Creed Taylor really liked the idea of taking classical music and adapting it to jazz or funk. This song gave me an opportunity to work with a larger ensemble of musicians. Especially for a piece like this, there was a huge orchestra and a big brass section. It also was one of the early recording sessions of Steve Gadd who became very respected in our field. He was one of the most well-known jazz drummers and “Night on Bald Mountain” featured him pretty prominently. Steve often credits this tune as helping him establish his reputation because so many people heard him on this. I’m very proud of that. Steve and I have remained very close friends since.

Creed Taylor really liked the idea of taking classical music and adapting it to jazz or funk. This song gave me an opportunity to work with a larger ensemble of musicians. Especially for a piece like this, there was a huge orchestra and a big brass section. It also was one of the early recording sessions of Steve Gadd who became very respected in our field. He was one of the most well-known jazz drummers and “Night on Bald Mountain” featured him pretty prominently. Steve often credits this tune as helping him establish his reputation because so many people heard him on this. I’m very proud of that. Steve and I have remained very close friends since.

Track #5: “Feel Like Making Love”

This song was written by Gene McDaniels. I was hired to play piano on Roberta Flack’s record and that’s where I first heard this tune. It was a great song and I had a feeling it could be a hit. We were in the studio recording her version, and within a couple weeks I had the opportunity to do my own record. So I just decided to use the same band, same sax player, same rhythm section; Idris Muhammad on drums, Gary King on bass, and Richie Resnicoff on guitar. So we were just trying to recreate that same groove, but as a funkier instrumental piece. I think it really work out great.

Track #6: “Nautilus”

This song is the most ironic thing of all. [laughs] It didn’t get any attention when the record came out in the ’70s. Then as years went by, I found out that the hip-hop field was heavily sampling it. Of course it was the LP era, so there’s a side A and side B. Often times, producers would put what they consider to be the best cut on the beginning of the A side because the audio is much better on the outer ring of a record. The grooves were wider and just other technical stuff like that. The songs that would be “attention getters” were placed on the outside of the record. And “Nautilus” is hidden at the end of side B. [laughs] So that should give you an indication that we didn’t pay much attention to it. I had written several compositions of my own, primarily so I could get my own copyrights of the album and this was just another one of those compositions. It’s a real simple tune because I was just looking for a nice groove to improvise on. I had a great rhythm section that was in the studio that day so we were just having fun.

III. “…the final say”

What has the sample clearance process been like throughout the years for you?

I’ll listen to the track that is sampling my tune. That way I can make an intelligent decision on whether or not I’m going to allow it. I still get requests for sample clearances all the time. It’s lessened through the years to a certain degree, but I still get requests to this day and it still surprises me. The coordination of the requests has become more well-organized, and simplified, than it used to be. We have a basic formula now for how we treat requests. Record companies are better about the approach nowadays because there have been too many lawsuits and they’d lose money if they did it the wrong way. Fortunately, almost all the records where there have been sample requests, I am the record company. [laughs] I am the artist, record company, and composer by law. So I control all the publishing rights and fortunately, make a lot of the decisions.

Are there any songs that you don’t have full control over?

There is really only one significant piece where I don’t have the final say, and that’s “Angela.” I don’t know if younger people remember, but it was used for the television show Taxi. I heard its also been sampled by some hip-hop artists recently, but the television company owns those administration rights. Of course, for a song like “Take Me to Mardi Gras,” they have to get permission from Paul Simon’s publishing company too, since I didn’t write it. Technically, I just control the recording of my version. So something like that is more of a joint effort, but that’s rare.

Have you heard how “Angela” was used? What do you think when you hear how your work is sampled?

I haven’t heard how “Angela” was used. Even if I didn’t like it, I couldn’t do anything about it anyways. [laughs] But I can’t say I’ve ever heard anything I’ve really disliked. I’m usually just very flattered when I hear someone else interpreting my work.

You’ve never heard something and thought your music got butchered?

Well, there have been a few songs that I’ve heard where my song was sped up so fast, or slowed down so much, that it didn’t even sound like my piece anymore. That can be kind of annoying. But I know why they want to do it, since they’re probably looking for a different tempo to fit with the rapping, or other samples they might of used. But when it distorts my records so much I wonder why they just didn’t get something else that fits better rather than Mickey Mouse-ing my tune. [laughs] There was a reason why we worked so hard on certain grooves and played things at specific tempos. When its changed too much, it gets at best, comical; and at worst, insulting. But that’s rare. I usually like interpretations of my songs.

What are your final feelings on being such an integral part of hip-hop’s history?

Nowadays, I live in Michigan and am still able to tour the world playing music. Life has treated me real well. Being a part of rap history is just another extremely good thing that’s happened to me in my career. I’ve heard about other composers of my era who don’t like their work being sampled or touched—but I’ve never felt cheated. I mean, sampling gave my work a life of its own without me being in the creative process at all. I’m just a bystander watching it happen. It’s a bit strange. [laughs] But it is a good thing because of the exposure. In many instances, it led hip-hop listeners who’ve recognized certain samples to dive into my original works. And seeing how sampling isn’t just a passing fad, or that it was done in a novelty kind of manner, makes me extremely flattered. I still don’t know why everyone chose my music to use. But here we are, twenty years later, and people are still talking about it. I’m very proud that my music has taken on this new life, and for the most part, thehip-hop audience and musicians have treated me with great respect. It seems like I’ve always gotten the final say throughout my career. You really can’t ask for anything more than that.