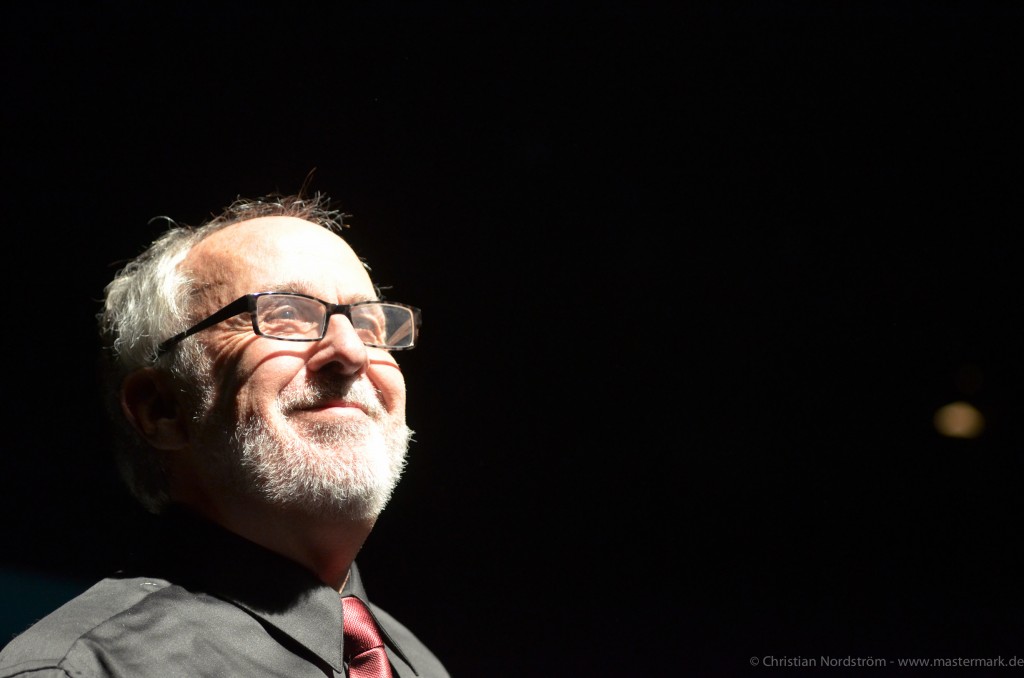

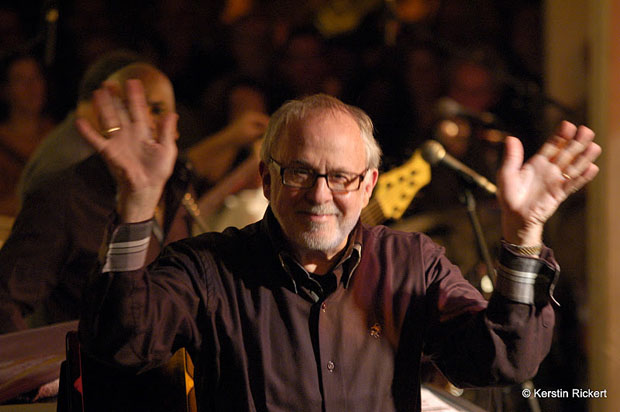

Bob James: It’s great to be speaking with you, Mike.

MR: Thank you very much, and thank you for spending some time with me today.

BJ: I’m speaking to you from Traverse City, Michigan.

MR: Is Traverse City where you’re set up? Is that where your label, Tappan Zee, is?

BJ: Sort of. Tappan Zee has dwindled down to basically being just an expanded version of me. It’s not really a record company, a big warehouse or anything like that. Traverse City is my home now, and most of the year it gets awfully cold here in the Winter time, so I escape down to Savannah for three or four months in the Winter time.

MR: It’s interesting that you haven’t mentioned a typical place that musicians go to, like New York or L.A.

BJ: Well, I lived in New York for many, many years, and I’ve recorded almost all of my projects either in New York or Los Angeles, so I end up spending time there. I don’t know, eight or ten years ago I discovered that it didn’t make that much difference where I started out from because I was going to be traveling a lot anyway. You’ve got to start from some place, and while it’s a little more complicated to start from Traverse City, there is cab service into Detroit and Chicago, and I can get almost anyplace from there.

MR: And there’s always the internet, of course.

MR: And there’s always the internet, of course.

BJ: Definitely. I use the internet a lot, and I do a lot of recording here, actually. Some of the guest stuff that I do on other people’s projects I can do here at my home studio.

MR: What kind of keyboards do you have in your home studio?

BJ: I use very prominently a Yamaha Disklavier. I have a seven foot C7 Yamaha that is a beautiful piano in and of itself, but I use the recording capability of it to record the data from my performance on the computer via MIDI. So, I can edit, and I can do all kinds of things with it. I can use the conventional piano as my main keyboard, and then interface with various synthesizers or software synths or whatever. That’s the main one. Then, I also have a Yamaha Motif rack. Since I’m a Yamaha artist, most of my keyboards are Yamaha keyboards too.

MR: Let’s get into your new album, Altair & Vega. These aren’t piano duets are four hands on piano. You and Keiko have been trying to do a project together for a while, right?

BJ: Yeah, we performed an actual tour about ten years ago over in Japan and then we did a few dates over in the US. I had invited her to play one song that I had composed for her on my album Dancing On The Water, which was actually the song, “Altair & Vega.” Then, she reciprocated by writing a song for me, which I played on one of her records. Our intention at that time was to expand it to a full project, but one thing did not lead to another, and we had scheduling and contractual complications. We’ve just been frustrated for the amount of time that we never really were able to put our hobby project together. We just kept being persistent about it, and eventually everything just came together. E1, the company that has put the album out, also agreed to what I think is a really wonderful bonus aspect of it, which is that it includes a DVD as part of the packaging. It’s especially important for what we do because the two of us playing at one piano is kind of impossible to visualize on a CD. You can’t put one of us on one speaker and one of us on the other, and there’s really no way for anybody to know who is doing what just listening to the audio. But when our fans see us, then they get it because we do a lot of what I guess you would call choreography–hand choreography. We cross hands a lot, and sometimes we even get up from the bench and switch places. It becomes a little bit of musical chairs, which we love, and all of that comes across on the DVD, and hopefully gives our listeners a chance to really understand what they’re hearing on the CD.

MR: Nice. So, on a song like “Altair & Vega,” was Keiko mostly on the upper part and you were on the lower part?

MR: Nice. So, on a song like “Altair & Vega,” was Keiko mostly on the upper part and you were on the lower part?

BJ: Yes, except that we do switch in a couple of places because there is an ad lib solo section in the middle, and in both cases on that particular composition one of us takes over solo while the other gets out of the way. When we perform live, we have two little chairs next to the piano, and when somebody is playing a solo section, then the other one gets up and becomes a listener.

MR: There’s a story connected to “Altair & Vega,” and that is that they are two stars that pass through the heavens, but only meet once a year.

BJ: Yeah, I heard about that story when I was trying to come up with a title for that song. It kind of unfolded when I learned that Keiko had accepted my invitation to be my partner on that piece. I learned a lot more about the history of it long after I had written the song and used the story as a title. I found out afterward that it’s tied in with a national holiday in Japan on July 7th–the seventh day of the seventh month, which in the folk tale is when the two stars converge. We’ve never gone so far as to play a concert on that date every year, but that would be fun.

MR: I think the holiday is called Tanabata.

BJ: Yes.

MR: Can you tell me what the creative process was like working with Keiko? You both collaborated on “Forever Variations,” so let’s start there.

BJ: Well, it basically was my four hand piece, but it was based on Keiko’s composition, “Forever, Forever,” which was already written and was included on one of her earlier albums. I set out to do that because one of the historically prevalent idioms of four hand piano music is theme and variation for whatever reason. Composers back in the eighteenth and nineteenth century wrote in this theme and variation style where they took a very recognizable melody, and then did as many variations as they could come up with. That was a very popular way to compose back in that time, and it was very much a part of four hand piano literature. So, that was my motivation to want to do something like that in the twentieth century–which now has turned out the be the twenty-first century–using what was a very familiar piece to Keiko’s fans, and then doing a whole bunch of variations on it. So, the variations are mine, the theme is hers, and that’s why it’s listed as a co-composition on this album.

BJ: Well, it basically was my four hand piece, but it was based on Keiko’s composition, “Forever, Forever,” which was already written and was included on one of her earlier albums. I set out to do that because one of the historically prevalent idioms of four hand piano music is theme and variation for whatever reason. Composers back in the eighteenth and nineteenth century wrote in this theme and variation style where they took a very recognizable melody, and then did as many variations as they could come up with. That was a very popular way to compose back in that time, and it was very much a part of four hand piano literature. So, that was my motivation to want to do something like that in the twentieth century–which now has turned out the be the twenty-first century–using what was a very familiar piece to Keiko’s fans, and then doing a whole bunch of variations on it. So, the variations are mine, the theme is hers, and that’s why it’s listed as a co-composition on this album.

MR: “Frozen Lake” has a story behind it too, right?

BJ: Yeah, it was just wonderful to watch it unfold, actually. We recorded the CD portion of this project here at my home studio in February, which is about the coldest time period. No surprise, it was very cold and the ground was completely white during the whole time we were working on the project. During one of the days we wanted to take Keiko down to the lake, which is right next to where my studio is. It was completely frozen and you could walk out on the lake. At that time of year people actually go ice fishing, where people even take little motorized vehicles out on the lake. So, we walked around, and she had never had that experience before or seen it, and she was very inspired by it. The next day we both thought that we might try to come up with some new material. Most of what we had planned for the project were things that we had already performed live over the last ten years, and we were just committing them to the recording, so it wasn’t a prerequisite at that time, but we thought it would be cool if we could come up with something new. I had an electric keyboard on the other side of the room and Keiko was on the big piano, and we both set out to do a piece. Several hours later we auditioned for each other the piece that we had been working on. As it turned out, I have to humbly admit that her piece was great and my piece just didn’t really come off. It ended up being called “Frozen Lake,” and that’s how it all came about.

MR: Then, you also have “The Professor And The Student,” which I’m sure doesn’t reflect the relationship that you have with Keiko.

BJ: Well, in a comic, sort of joke-y way, it did because I’m considerably older and took on the role of the professor. That actually came about as a result of another piece by Haydn that was a theme and variations. The concept of that piece was the professor teaching a piano lesson to a student. The way that Haydn wrote it was that the them would first be played by the professor, and then repeated by the student who was trying to learn the phrasing from the professor, and the piece kind of unfolds that way. I took that as a sort of jumping off place, using the very basic Haydn theme at the beginning, and then in my adventure the student actually starts to become better than the teacher. You don’t exactly hear it when you listen to the piece because you can’t tell who is doing what, but as the piece unfolds, the student keeps getting better and challenges the teacher to kind of keep up by the time they get to the end of it.

MR: Pretty smart stuff. It seems like over the last few decades, there have been fewer and fewer artists that have a background in classical music. Do you feel it’s important to have a classical music education as a backbone for whatever creativity an artist will need to express later?

BJ: I can only say that during my whole education process and the way that I’ve always felt about it is that there isn’t an equivalent curriculum in music education that can compare with the history of classical training. In my way of looking at it, the depth that any musician can get from a classical background forms the basis for a much broader understanding of music that can be applied to any stylistic direction you end up wanting to go in. Even in jazz, which is my area, there are a number of really good jazz schools, and I know there are a lot of people who believe in that, but I think it just narrows focus. So yes, I regret that classical music and other more traditional forces in education are being threatened by the changes that are going on in our society. I’m a traditionalist in that respect for sure, and I hope that it doesn’t become lost on the younger generation.

MR: I normally save this question to the end of a conversation, but I think it fits nicely here. What advice do you have for new artists?

BJ: Well, it would be right along those lines. I don’t believe there are any shortcuts, so the better prepared you are, the better your chances of having a successful career. I hear a lot of young artists talk about needing to get a break–I believe that everybody gets the break, but it’s a question of what you do when that break happens. Many people that I see struggling are not as prepared as they should be when that time comes. Getting a break can mean many different things. It can just be having the right person hear what you do at the right time and word of mouth takes over, which is a very powerful part of our field. I’ve seen it happen so many times when somebody seizes that moment when the break happens, and just show off what they’ve done with all that hard work and preparation. The upside of that is limitless. The laziness that I see happening with people that are looking for shortcuts or people who have misinterpreted what they see on television–they can sort of make it look really easy to do those things that successful people do, when in fact it really isn’t. To me its no shortcuts. Work hard and be realistic about what you instinctively know is your gift because that’s different for everybody. Not everybody is destined to have the talent and instinct to be a performer, and there are people who no amount of practice will ever make that a possibility. They love music and they’d love to be able to do it, but it’s just not in the cards for them.

MR: That may be one of the fullest answers I think I’ve ever gotten to that question.

MR: That may be one of the fullest answers I think I’ve ever gotten to that question.

BJ: Well, really nobody knows the answer. There are exceptions all the way down the line of everything that I’m saying even. There certainly are people who become instantly successful with seemingly very little effort because they happened to be able to do the right thing at the right time to grab the attention of a large audience. I can only sort of generalize based on seeing a lot of different situations go down. If you want to be a realist and not have to limit yourself to being one in a million, the realistic person prepares as much as they possibly can. I think that will always serve you well no matter what you end up doing.

MR: Now, you are someone who was able to catch a decent break back in the ’70s when the show Taxi used your song, “Angela.”

BJ: There’s an example of timing being everything. It’s the only TV show that I ever wrote the music for, and it came to me, I didn’t come to it. It was very much a result of very good fortune that the producers of that series had one of my records in their collection. They were playing it as an experiment when they were working on trying to establish a mood for the show and it seemed to fit the mood that they were looking for. They ended up seeking me out to ask if I’d like to write the music. It was a brand new kind of experience for me. At that time, I wasn’t really doing much radio or TV music. I had some experience with that prior to this, so at least I knew technically how to go about it. I knew they were looking for something that was different than standard commercial music, so I took a different approach, which was to treat it just as though it were another record album. I told them that there was no way I was going to get that same kind of mood on a ten or fifteen second music cue, so I just went and recorded some four and five minute pieces with a very similar band to what I would have used in a jazz set, and then I worked with the editor and producer to take little snippets for certain things that were happening in that show. It worked out great. They loved the idea because it gave them kind of a library of music, and we weren’t sitting there with a stopwatch trying to make the music fit the action.

MR: Having lived in New York during that era, the music I remember hearing in actual taxi’s was either rock ‘n’ roll or jazz music.

BJ: The first piece that I thought of–I actually submitted it in the first session, thinking that it might become the main theme–was an upbeat, frenetic, high energy piece. I was thinking about the car horns, traffic jams, and what I was perceiving as a New York atmosphere that they’d want to be generating on the show. It turned out that they had a very different vision. They had this image of the taxi going across the bridge at dusk, where it was a very quiet, mellow mood, and they didn’t want to use the piece that I submitted. In the meantime, though, I had written this other piece that I thought would just be a background, melancholy piece to be used in one of the episodes. They said, “That’s what we’re looking for in the main theme. Would you mind if we switched and used that.” Of course, I was just happy that they liked it. A lot of the history of how that came about was really just good fortune and accidental.

MR: Another of your most well known pieces is “Nautilus” because of its sample usage.

BJ: That whole development is crazy, and I still don’t understand it to this day, that this part of my music history ended up in the rap/hip-hop field not by me doing anything about it consciously; it just got chosen. It’s flattering, sometimes frustrating, sometimes on the edge of being thievery. I’ve gone through every variation of what to think about it, but for the most part, it has ended up being extremely flattering, and a way that a lot of young people get a chance to know my music that wouldn’t have that chance otherwise.

BJ: That whole development is crazy, and I still don’t understand it to this day, that this part of my music history ended up in the rap/hip-hop field not by me doing anything about it consciously; it just got chosen. It’s flattering, sometimes frustrating, sometimes on the edge of being thievery. I’ve gone through every variation of what to think about it, but for the most part, it has ended up being extremely flattering, and a way that a lot of young people get a chance to know my music that wouldn’t have that chance otherwise.

MR: Another way people may know your music is through some of your Grammy-nominated works. For instance, you’ve won Grammys for your collaboration with Earl Klugh on One On One and also for your work with David Sanborn on Double Vision.

BJ: The Grammys are a great marketing tool, for sure, and I have thirteen nominations to go along with those. You just keep cranking out the stuff and hoping you get the nod again. Awards, to me, are wonderful when you win them, and not so meaningful when you lose them.

MR: You also have produced a couple of my favorite albums, especially Kenny Loggins’ Celebrate Me Home. It was such a breath of fresh air at the time. You also produced the followup, Nightwatch.

BJ: Yeah, it was great timing for me to meet Kenny because on his first solo record, he had just kind of broken up the Loggins & Messina thing and was getting ready to do something on his own and I had just gotten an A&R job at Columbia. Kenny decided that he wanted more jazz influence on his project and for somebody with a jazz background to help him, and he found his way to me. At that time, I hadn’t ever met him, and I wasn’t too involved in the folk-pop era, so I had to play catch up to learn about his music. It was fascinating to discover how much he knew about jazz and how much he respected it. It was a great opportunity for me.

MR: There were so many wonderful tracks on Celebrate Me Home, like “Why Do People Lie,” “Set It Free,” “Lucky Lady,” and of course, the title track.

BJ: Just talking about this is flooding back the memories for me because I hadn’t scoped that out too much recently, except that the guitar player for Fourplay, Chuck Loeb, his daughter, Lizzy Loeb, just recorded “Celebrate Me Home” on a project of hers that I just listened to last week and she sang it great. She does a beautiful version of the song, and it made me feel great to hear it and see how the song has taken on a life of its own even away from Kenny’s version.

MR: You know, you’re credited with being one of the founders or forefathers of smooth jazz.

MR: You know, you’re credited with being one of the founders or forefathers of smooth jazz.

BJ: I get it both ways–I get the credit, I get the blame, and I’m sometimes not even the forefather because I’m the grandfather, so there’s an age factor in there as well. I don’t know, that’s something that I certainly wasn’t thinking anything about at the time. I know that I was around when there was a fairly big movement unfolding in jazz that was a significant break from swing–or a different way of thinking about swing–and a different way of thinking about guitar, and a different way of thinking about bass. It was shifting over to being electric bass. I got many, many gigs playing electric piano, and that sound was different. I just happened to be there, and I was getting a lot of recording dates and playing with a lot of different people around that time. I was interested in it too because I was becoming frustrated and even bored with the way that straight ahead jazz was going because a lot of it was sounding the same to me, and a lot of artists were trying to recreate the bebop era. To me, it had been done so well with so much freshness and excitement in the era that the music was created in that it was time to do something else. To me, because jazz was an improvised music, it had to be ever changing. There was no perfect or correct way to play jazz–I still feel that way. It must be always changing, otherwise it goes into the museum. So, in that sense, if I became one of the people that encouraged that and explored it myself? Then, yes, I plead guilty.

MR: You’ve also had a lot of success with Fourplay. When you guys get together, do you just jam and make a record, or does each person bring a piece and arrange it out?

BJ: All of that. It turns out that the longer I’m in this group, the more I realize how unusual and unique our concept was. I’m sure there are other democratic groups, but we really specifically set out to be four people with no leader and all of us are equal. In our concept, we were sidemen and we were leaders depending on which song we were working on. We tried to balance and have on all of our albums who composes and arranges stuff. At its best, it’s fantastic–it’s a very truly democratic thing. At it’s most frustrating, any time there is a really difficult decision to make, all four of us run and hide because none of us want the stress or difficulty of making a decision that may not be fun for any of us. Those are the hardest times, when the voting process can become a stalemate. For the most part, though, it has been an incredible opportunity to be part of a team, and to be able to relax. For me, having only twenty-five percent of the responsibility is a relaxing and fun way to make music. I know there are times when I’m going to have to go to the forefront, and a lot of other times when I can just go along for the ride.

MR: Let’s get back to Altair & Vega and talk about “Bach Chorale.”

BJ: I actually wrote that arrangement as a Christmas present. Keiko was, at that time, doing a Christmas concert in Japan every year, and she had invited me to come over as a guest, so I wanted to have something special for the concert. Again, in the piano duet literature, a lot of it is based on either themes and variations or on adaptations–re-arrangement or re-orchestration–of a familiar piece that was originally written for a different instrumentation. There are a lot of arrangements of symphonies, for example. There are piano arrangements of all the Beethoven symphonies and many of the Mozart symphonies. It was done that way in that time because it was too difficult for one pianist to do it. There was too much to cover with all the stuff the orchestra was doing, so they would cut two pianists to give a more accurate rendition of what the music held. Also, they didn’t have stereos in that era, so if the symphony orchestra didn’t come to your town, the only way you could hear this symphonic work was through these arrangements, which were often arranged by the composer, but were often done by somebody else. So, in this case, I just took one of the very famous Bach chorale’s and arranged it for a piano duet. It was a very fun challenge–Bach is one of my very favorite composers–and he didn’t write piano duet music specifically for that repertoire, so for us, it gave us the opportunity to play Bach in the four hand piano setting.

MR: Before we run, I wanted to ask you about Sarah Vaughan. You spent some time with her in the beginning. Would it be fair to say that she’s one of the people who launched you?

BJ: Absolutely. It would be more than fair to say that. Sarah became an unbelievable opportunity to be introduced to people that I never would have met otherwise. I spent four and a half years with her on the road, and met people like Billy Eckstine, and on and on and on. The word of mouth became vitally important to me. Also, just being able to use her as my calling card, on my bio, on my resume was very major because Sarah had ultimate respect in the jazz field, and the fact that she chose me to work for her was just a really great opportunity. In addition to that, I always refer to that time like a second college education. I felt a tremendous amount of power being her accompanist. She was quite moody, and when she was inspired, the degree of genius that she would display on stage was just unforgettable. She could also become bored pretty easily or pretty angry if what was going on behind her was not inspired or not what she was looking for. So, I learned that if I did my homework and came up with something good, and if the trio was grooving, then we became this cushion for her to take off and do her thing. It was awesome to hear it, and I felt like I had this power to participate in it because the difference between when I would get my act together or not was the difference between when she would do what she was capable of.

BJ: Absolutely. It would be more than fair to say that. Sarah became an unbelievable opportunity to be introduced to people that I never would have met otherwise. I spent four and a half years with her on the road, and met people like Billy Eckstine, and on and on and on. The word of mouth became vitally important to me. Also, just being able to use her as my calling card, on my bio, on my resume was very major because Sarah had ultimate respect in the jazz field, and the fact that she chose me to work for her was just a really great opportunity. In addition to that, I always refer to that time like a second college education. I felt a tremendous amount of power being her accompanist. She was quite moody, and when she was inspired, the degree of genius that she would display on stage was just unforgettable. She could also become bored pretty easily or pretty angry if what was going on behind her was not inspired or not what she was looking for. So, I learned that if I did my homework and came up with something good, and if the trio was grooving, then we became this cushion for her to take off and do her thing. It was awesome to hear it, and I felt like I had this power to participate in it because the difference between when I would get my act together or not was the difference between when she would do what she was capable of.

MR: I don’t think I’ve ever heard a story like that about her before.

BJ: There were so many things I was learning. Number one, I loved being an accompanist. In many ways, I like it better than being out front as a solo artist. I don’t think it’s been accidental that the only two Grammy’s I won were in collaborations where I was functioning a lot of the time as an accompanist. It’s the same thing with Fourplay–it’s a major part of what I do in that group, and I’m proud of my contribution as an accompanist even in that setting. It probably started back in that era, when I learned that I could be successful at the keyboard in that role and enjoy it.

MR: This has been a really great conversation with you Bob. Thank you, again, for taking the time to speak with me today. Definitely, let’s do this again.

BJ: I’d love to, and Mike, it’s wonderful to have the opportunity to talk about this project, Altair & Vega. Keiko and I are both very proud of it, we’ve been nurturing that material for ten years, which is very unusual for a recording project anyway, to have the recording take place so far down the line, after you’ve already gotten to know the material. We know that it’s such an unusual genre that we need help getting it introduced to the public. Most of the fans that know Keiko’s separate music and my separate music don’t really know much about four handed piano duets. So, we’re hopeful that they will go beyond what they are accustomed to hearing and enjoy the adventure of hearing this record, which is really quite different.

MR: Yes, it’s a first for me. Bob, thank you again for visiting with me today.

BJ: Okay, Mike, it’s a pleasure talking to you.

Tracks:

1. Altair & Vega

2. Frozen Lake

3. Divertimento

4. Midnight Stone

5. Invisible Wing

6. Forever Variations

7. Bach Chorale